We constantly use our sense of smell to perceive odors around us. The genes we use to smell were only discovered in 1991 by Linda Buck and Richard Axel, who won the Nobel Prize for their discovery in 2004. That means that humans have been on the moon before they even knew how they smelled.

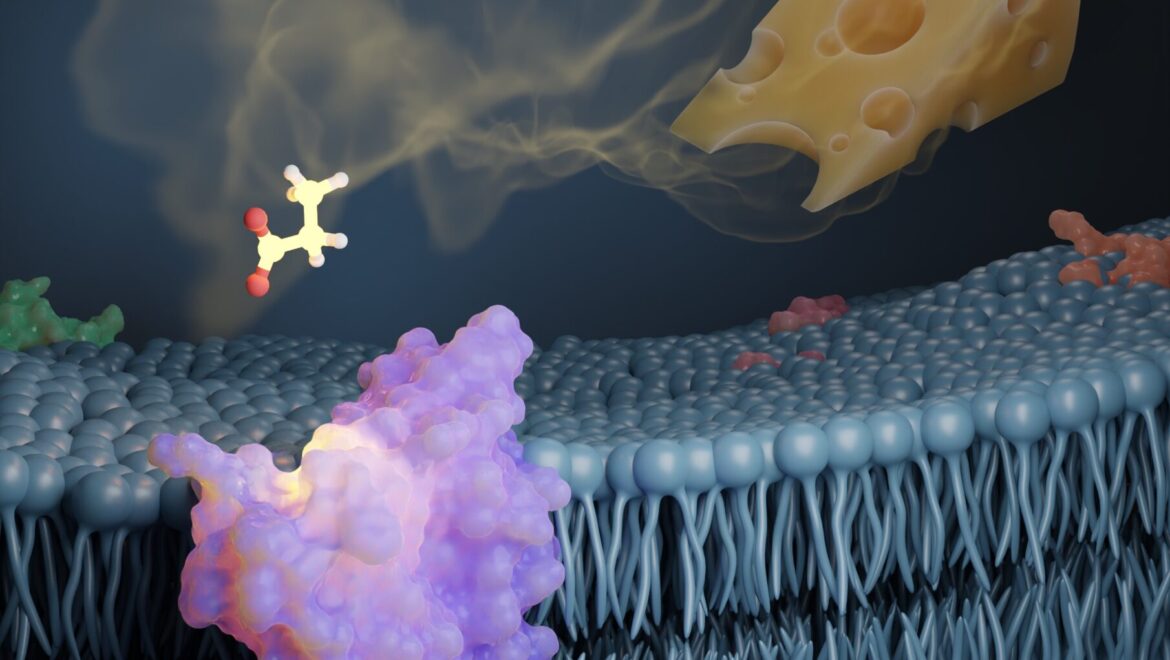

These genes code for the odorant receptors (400 in humans) which are used to smell from 10,000 to more than a billion odors. Moreover, these odorant receptors are also expressed outside the olfactory system in cancer cells, the skin, the lungs, and the spermatozoa. Therefore, they seem to play an essential role in our body outside the perception of odors. In the sense of smell, these receptors capture odorant molecules and are activated in a combinatorial code that is specific to each olfactory perception. Researchers have been trying to elucidate the experimental structure of these receptors for decades, without success because of the difficulties encountered during their production in a cell models. Thanks to advances in structural elucidation methods and careful choice of the odorant receptor, Claire de March, in collaboration with Duke University, the University of California San Francisco, and City of Hope, finally succeeded in obtaining the first structure of a mammalian, and more particularly human, odorant receptor: OR51E2 linked to the propionate, a molecule with a cheese smell.

Published in Nature, this study finally allows us to have an idea of what these receptors, which we use every day to smell, look like. And we can already say that they are unique because they present parts structured in a way that does not have never been observed before in other non-olfactory GPCR. This is a very big step forward for the field and towards understanding how we perceive odors.